为storytelling collective网站的课.

那个网站集合了比较新新的…游戏/桌游剧本的作者,挺有意思.

因为节约时间(偷懒)大部分就copy&paste了.

中篇.

Writing tools

- Your writing tool of choice.

- A calendar to track your deadlines.

- Optional, but encouraged: A project management tool to document your notes and track your progress.

Key: keep everything simple.

Additionally, we do not recommend writing directly into a layout tool like GM Binder or Adobe InDesign.

Storytelling Collective Recommended: Microsoft Word (and comparable alternatives like Libre Office or Pages).

It’s not because we think Word is the best program of all time — it’s because most people have access to it (or a version of it), most people know how to use it already, and its accessibility tools transcend those of other programs.

More Options:

- Google Docs

- Ulysses

- Scrivener

- World Anvil

- Physical Notebook

Brainstorming

Ultimately, you should get comfortable coming up with a lot of bad or mediocre ideas before getting to a gem.

As writers, we have to learn how to be less precious with ideas.

Not every concept we have is “the one,” but it’s only by getting them out of our head and practicing this process are we able to identify what we think of as our own good ideas.

And when we can better identify the truly good ideas, we’re more likely to complete projects and set reasonable project scopes and timelines.

Quote by NPR host Ira Glass:

Nobody tells this to people who are beginners. I wish someone told me.

All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap.

For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good.

It’s trying to be. It has potential.

But your taste — your taste is still killer.

And your taste is why your work disappoints you.

A lot of people never get past this phase. They quit.

Most people I know who do interesting creative work went through years of this.

Our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have.

We all go through this. And if you’re just getting started or you are still in this phase, you gotta know it’s normal, and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work.

Put yourself on a deadline, so that every week, you will finish one project.

It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap and your work will be as good as your ambitions.

It’s gonna take awhile. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.

There’s no shame whatsoever in writing five sentences (or five pages) of a story before deciding that it’s not going to click after all—you’ll know you’ve found ‘the one’ when it keeps popping into your head, and you keep thinking of more places you could go with it.

Plus, sometimes you’ll come back to one of those stories you started, and suddenly have a great idea of how to finish it.

I’ve put plenty of half-finished stories aside, only to come back years later and find my way to the end of them.

Brainstorming Toolkit:

- Use existing tabletop RPG resources.

- Emulate your favorite stories.

- Develop an archive of past ideas.

- Use maps, photographs, music, and art as inspiration.

Moodboards

A moodboard is, essentially, a visual overview of your story concept. You can create one moodboard that encompasses several elements — characters, setting, challenges — or create separate, more specific boards.

这个挺有意思的,记得高中美术课也有做过类似,收集图或者字,段落,音乐,任何其他的作品,作为印象素材.

Resources for Creating Moodboards

- Unsplash/Pexels/Pixabay: Free stock images

- PicMonkey: Collage templates and image editing tools

- GoMoodboard: A free mood-boarding tool

- Canva: A user-friendly graphic design tool for beginners

- Adobe Spark: Free graphic and moodboard maker

- Pinterest: Arguably the most popular moodboard-maker

A moodboard is so valuable because it becomes an easy source for prompts. If you’re stuck on what to write, describe something in your moodboard.

Structure

Introduction

This section that follows includes everything Game Masters need to get started with your module.

Background

What happened in the setting of your adventure that now requires characters to solve a conflict, explore, or investigate?

Overview (also referred to as Synopsis in some game systems)

What conflicts and plot twists does the Game Master need to know to properly facilitate this adventure with their table?

Because one-shots are self-contained — meaning, they have a clear beginning, middle, and end — it’s important for GMs to know the “goal” of the story.

This is where your synopsis comes in, which should be an overview of your story and the main goal of it.

NOTE: Unlike a full campaign, in which writers have the freedom to provide many options and outcomes, a one-shot is typically a bit more limited.

This doesn’t mean that there isn’t ample opportunity for role-play and exploration, but that the players will be more focused on completing the story.

Many new writers often worry about “railroading,” which means providing one specific way for the narrative to unfold rather than accounting for lots of character choices.

But you know what? It’s OK if your first one-shot is a bit railroad-y.

Write the story you want to write, and as you learn more about game design, you’ll be able to think more creatively about how to let stories play out without forcing it.

Adventure Hooks*

This is how the players can get involved with the story.

Some RPG writers write extensive adventure hooks; others put less thought into this, knowing that it’s ultimately up to the GM. Ideas for adventure hooks include:

- Overhearing a rumor in a tavern;

- Receiving a letter from a mysterious stranger;

- Randomly stumbling upon old ruins;

- Getting “lost” in the wilderness and encountering someone who gives the characters a quest.

You’ll likely include notes for GMs throughout the module, but the introduction is a great place to give GMs ideas to keep in mind.

For example, is there a certain atmosphere the GM should evoke (like, the whole story takes place at night)?

Is there a sense of urgency they should aspire for?

Body

This is the “meat” of your story and where you outline the narrative “beats” of it.

For a one- shot, thinking in chapters is useful. (Some writers call these “scenes.”)

And as you’re starting out, plan for three or four chapters.

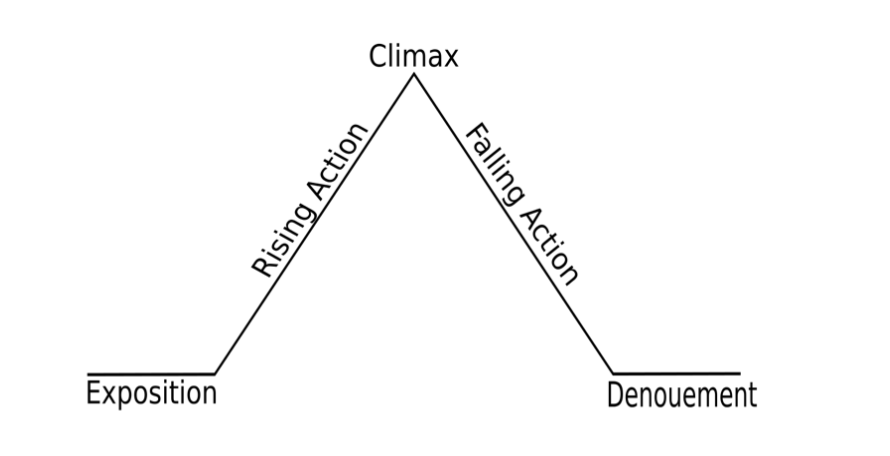

Are you familiar with “dramatic structure”? (Shout-out to my fellow English grads!)

This is, essentially, what comprises the elements of a story.

Freytag’s Pyramid easily demonstrates this:

So your chapters might be broken up as follows:

Chapter 1:

Exposition: Setting the scene (literally).

Where are your characters, who do they meet, and what are they doing?

Rising Action part 1: What is the “quest” they’ve been given?

Chapter 2:

Rising Action part 2: What happens once they embark on their quest?

What do they do and encounter?

What challenges are presented to them? This is where the tension is built.

Chapter 3:

Climax: What is the final challenge they need to overcome to complete the goal and the story?

This might be a boss battle; an escape from a quaking mountain/volcano; a rescue; etc.

Not every game needs to end in an epic battle, although that’s certainly OK too!

Falling Action: What are the consequences of what has transpired?

Denouement: The conclusion and epilogue of the story.

Optional Additions

- Tactics: It’s helpful for GMs to have some ideas for how to best use the enemies in battles.

- Motivations: For both ally and enemy NPCs, it’s useful for the GM to know what motivates their actions so they can role-play them to the fullest.

- Lore/mythology/world-building: A one- shot can be part of a bigger story and bigger universe. Include tidbits of lore throughout your module to give the GM context for how this story fits in to a larger narrative.

- Optional side quest: If you have an idea for something that might be fun that doesn’t necessarily fit in to your main story, you can include it as an optional side quest. This shouldn’t dominate your main story, but may provide another route of exploration for players.

Maps

This includes statistics for any NPCs, creatures, places, or items the characters encounter.

You can also opt out of maps entirely and allow the GM to focus on “theater of the mind.”

If you choose to go this route, be sure to describe in clear detail what the players are seeing and what the layout is of wherever they are (including directional/dimensional information, such as how wide a precipice is, how long a tunnel is, etc.)

Scope

Every time you have a new idea, you should set a project scope for it.

Scope is about giving yourself a chance to succeed.

“Scope is the defined features and functions of a product, or the scope of work needed to finish a project.”

Scope involves “getting information required to start a project” and the tasks needed to complete a project.

Setting a project scope means determining the following:

timeline

deliverable.

What’s the final “output” of this project?

list of to-dos

list of potential challenges or obstacles

这节课的一直在反复说服“要多做多写”,不要钻进一个点子出不来。

The best way to improve as a writer is to learn how to ideate frequently; vet your own ideas; set reasonable project scopes so you can complete the projects you commit to; share that work with others; and then… do it all again!

It is not one project that makes or breaks a writer.

Your most ambitious ideas are possible when you understand how you work and what your process is.

You should not burn out trying to finish a creative project; adjust as needed so that you can be creative long-term in a healthy, sustainable way.

课中建议的是四周,3,500 字的one shot模组.

It’s important to set a SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timely) goal for the month to keep you accountable and to start planning for the days ahead.

This equates to roughly 7 pages (if you’re using 12-point font, single-spaced, on a standard 8.5 x 11 inch page size).

What is this project and what is the final deliverable?

(Eg. “I’m writing a one-shot adventure set in Ravenloft. It will be a PDF document available on DMs Guild.”)

By when does this project need to be completed?

Do you need to learn a new skill or tool to complete this project?

Have you started learning that skill or tool prior to starting this project? (Explain yes or no.)

Have you completed a project of this size and scope before?

(If yes) What is one thing you’ll do differently for this new project?

How much time can you devote to this project every day, week, or month until it’s finished?

What potential obstacles may you encounter during this project?

Based on your responses, map out a timeline for this project.

(Be sure to add specific milestones with tentative deadlines.

Think in milestones instead of tasks; for example, “finishing an outline” is a milestone, whereas “complete lesson 5 activity” is a task.

The timeline is not a retread of the course calendar.

Your timeline is specific to you and when you plan to complete steps and milestones.)Is the timeline you’ve mapped out reasonable and achievable?

(Be honest!) If not, revisit your timeline now and adjust.

Summarize your project timeline.

(Include the final deliverable, potential obstacles, and the tentative project timeline. You do not have to summarize your adventure itself; this is just a summary of the logistics.)

Based on this summary, are you ready to begin your project and stick to this scope?

Themes and motifs

There are thousands of ways to tell one story, and the hallmarks of a genre are what make them so beloved.

According to MasterClass, there are 14 “main” literary genres:

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery

- Thriller

- Horror

- Historical

- Romance

- Western

- Bildungsroman

- Speculative Fiction

- Science Fiction

- Fantasy

- Dystopian

- Magical Realism (which is specifically a Latin American literary tradition) and Fabulism

- Realist Literature

Hierarchy:

genre -> theme -> motifs -> tropes

Motifs are recurring patterns that help to enforce a theme in your story.

The main difference is that symbols tend to be concrete and tangible expressions of an idea (like a small potted plant your NPC carries around the wasteland), whereas motifs tend to be more abstract (pockets of green overgrowth that signal signs of life or resources for your players).

Adjacent to these concepts is a “trope.” In storytelling, a trope is a “common or overused theme or device.”

What themes and motifs do you enjoy in your favorite stories?

What themes and motifs do you most enjoy exploring in your own storytelling?

What is a common trope that can be found in your favorite genre?

What is a common trope you can remix in your adventure?

Conflict

Not all conflicts need to be violent.

A conflict in an adventure is when the players feel like they need to pass an obstacle to move the story forward or find a resolution.

Type of conflicts, such as

- Villain

- Environmental

- Protection

- Infiltration

- Negotiation

Villain

The most common and self-explanatory conflict of all: an evil person must be stopped.

This conflict relies on having an NPC trying to accomplish something nefarious, and the party working to stop them.

Environmental

Conflict relies on the environment interfering with the character’s mission, be it by passing through a dangerous terrain, sliding down a mountain, or trying to catch a thief while running through a gigantic tree like in this Ryuutama scenario.

These types of conflicts are rarely used as the main conflict in any adventure, being relegated to small obstacles that the players must pass through in order to reach the main conflict.

However, a fun and unique approach is to make an environmental challenge the main obstacle.

Perhaps the characters encounter a villain within a volcano in Chapter 2, and upon the villain’s defeat, the volcano trembles.

Escaping this treacherous mountain about to erupt becomes the real challenge!

Protection

If you want an adventure that includes combat, but don’t want the players to be the ones attacking something, a protection conflict is quite useful.

Characters protecting an NPC from dangerous foes puts them in battle situations, but the focus of said battles is not to kill all enemies; the focus is whatever or whoever the characters must protect.

This shift is not very common and is sometimes causes characters to change their entire battle strategies, which makes for quite interesting stories.

Infiltration

This conflict, as well as Negotiation, are the hardest ones to write.

An infiltration conflict rises, for example, when the character wants to perform a big heist.

This is a challenge to design because it requires having a location/organization that presents a challenge to infiltrate, but still gives the players the ability to achieve a successful heist.

You must write enough clues and tricks the players can use to perform an infiltration, but can’t have the entire infiltration to depend on one thing, because as is the nature of TTRPGs, the players can fail at it, resulting in a very short conclusion to the adventure.

Negotiation

Negotiation conflicts can range from achieving an alliance between two warring kingdoms to convincing the lord of a town to finally take the goblins in the mines seriously.

As stated above, this conflict is hard to write, especially if you’re writing a 5e adventure which is a system that lacks some social rules.

This means you’ll have to create rules of your own to fit your adventure most of the time, or make clever use of lesser-used ability checks. But apart from that, negotiation conflicts can be extremely stressful and have the players on the edge of their seats because it requires the players to change/manipulate at least one person to do their bidding. And the wait for the final decision of such a conflict is nail-biting!

Setting

Setting serves as the backdrop for the action that happens in an adventure, and often contributes significantly to its atmosphere.

It describes the locale in which an adventure occurs, including time, place, and environment (both physical and social).

The purpose of setting is to provide context and improve the player experience while adding to the adventure’s development with plot, mood, and NPCs.

Ask yourself: What are the important details in an adventure setting that are relevant to the action?

Remember that the setting of a story includes more than the terrain, weather, and climate.

Things to consider are the who, what, where, why, when, and how of a locale.

When asking yourself these questions about setting, a natural addition should be: How do these things affect the PCs and NPCs?

On a macro level, consider how the environment and geography may have an impact on local customs, laws, behaviors.

A desert location, for example, may cause inhabitants to value water as a commodity or even drive their technology toward aqua farming.

On a micro level, consider the important NPCs and the “General Features” of a specific area where the adventure takes place.

These include the minutiae like light source, ceiling height, creatures in the area, etc.

Information must be presented in a concise and easy-to-navigate format.

Sidebars are useful when providing backstory or lore for the Game Master to use within the context of the adventure and to allow players to discover information during their interactions with the environment.

When writing boxed text, refrain from using second person as it may accidentally remove player agency and be sure to include relevant details only.

| Where does the adventure take place? | |

|---|---|

| What is the environment of this location? | |

| How does the location impact the people in the area? | |

| What are the significant cultural, political, or other social conditions like here? | |

| When does the adventure take place? | |

| Why would the adventuring party be here? | |

| Who are the important NPCs? |

Villain

Character vs Character

This occurs when two characters oppose one another.

The reasons for this can vary considerably based on the motivations of the characters involved.

However, it’s important to note that a villain will rarely see themselves as such, and may have some sort of justification (usually flawed) for their actions.

For the purposes of our games and modules, this sort of conflict will usually be between the PC(s) and one or more NPC characters.

Examples:

- An assassin trying to murder an important noble the PCs are protecting.

- A rival knight in a tournament the PCs are participating in.

Character vs Self

This occurs when a character engages in an internal struggle.

Characters might need to grow in skill or knowledge to overcome a difficult obstacle, or might face a moral dilemma which prompts reflection and personal growth.

This is less easy to implement in a TTRPG or adventure module, but can be done by using the villain to manufacture a situation for character development or skill-building.

Examples:

- A wizard who demands the PCs succeed in a series of complex tests before he will agree to take them on as apprentices.

- An evil warlord who tempts the PCs with promises of power and wealth they desperately want.

Character vs World

This occurs when a character is opposed by a greater force.

This could be society, nature, god, magic, or advanced technology.

This conflict is marked by a sizable power imbalance between the character and the outside force.

The character shouldn’t be able to “stop” this force entirely, but should be able to overcome it in a limited way, weaken it, or simply survive it.

In our adventures, this sort of villain might be the head of a large organization, a deity, or something else equally powerful.

Succeeding against this villain would not mean a total defeat of the villain, but rather the PCs accomplishing their goals despite the villain’s interference.

Examples:

- A plague spreading through a city the PCs are trying to save.

- A town of people who wish to prosecute the PCs for a crime they did not commit.

When in doubt, a wonderful first step to creating a functional villain is to establish a clear and present threat posed by them.

RATS System

Relatable.

The players should be able to relate to the villain.

The villain doesn’t have to be likable or well-received, but you can do so if you want to use a sympathetic anti-villain as your antagonist.

The main point here is that the players understand why this character is a villain.

Providing a reasonable and compelling motive helps tie the villain into the greater narrative of your story, and creates a reason for the players to follow the adventure and act against the villain.

If your villains aren’t relatable, then they lose out on personality and become more faceless and ambiguous.

If that happens, your story conflict will more closely resemble a character vs world structure, and the villain will become less important to your narrative.

Antagonistic.

The villain should actively work against the players.

In doing so, they will remain important to the narrative, and the players will remain engaged.

The villain doesn’t have to be behind every single misfortune the players find, but it should be clear that the villain’s interests are directly opposed to those of the players.

If your villains aren’t antagonistic, they become passive participants in your narrative and lack clear direction and serve little purpose in your adventure.

Threatening.

Villains should be threatening.

They don’t have to be all-powerful, but they should at least have some niche where they have the power to cause harm to the players in some way.

Maybe they’re physically imposing and can kill with ease, or perhaps they can cast powerful spells that could debilitate the players.

Or maybe they just have friends in the right places who can make life difficult for the party.

If your villains aren’t threatening, they aren’t going to be taken seriously by the players.

At best, they’ll be a minor annoyance.

Special.

Your villain should be distinctive and interesting.

A unique style of dress, manner of speech, special power, impressive equipment, or anything else can set them apart.

The goal here should be to make an impression on the players with some quality of the villain’s character.

Doing so will make them memorable for the players, which leads to them understanding and enjoying your adventure.

Having a villain that doesn’t feel special will lead to a lack of interest by the players, which tends to undermine the enjoyment and success of the adventure.

NPC

An ideal NPC is mechanically functional, emotionally resonant, and memorable to the players.

NPCs provide information on the world at large.

They live here.

Their profession, age, clothing, attitude, and more set the tone for the adventure’s environment.

You can put in a box of read-aloud text detailing how everyone is downtrodden and the landscape is grey, or have a down-trodden NPC comment on how colorful, cheerful, and out of place the party seems.

NPCs provide direction to characters.

A good rule of thumb is that if your NPC has a name, they must have a purpose.

Everyone in a village does not need a name.

Everyone in a tavern does not need a name.

In a town of 400 villagers dealing with a hag, good people to name would be the hag, a villager working for the hag who will mislead the party, someone afflicted by the hag’s curse, and a witness to some chicanery.

These characters all serve the goal of guiding the characters, even if they’re guiding them to an incorrect conclusion.

The farmer who minds their own business and has no dealings with anyone is someone you can trust the DM/GM/Storyteller to come up with on their own.

When crafting your NPC, think about what they most want, what would be the worst outcome for them, and what secret they’re keeping.

The D&D character creation method of Traits, Bonds, and Flaws is another way of addressing this.

A useful guideline is to give each NPC a goal, a fear, and one other attribute (a quirk, a secret, a “rage button,” etc.)

Be sure your NPCs goals, fears, and quirks are relevant to the adventure at hand.

Ideally, a good character has something that makes them memorable.

In a world where everyone has a high fantasy name like Aelfywhyn Glinhymfyar, Beans the Pirate Cat is going to stand out.

An NPC who breaks tropes and surprises adventurers is more likely to be memorable, whether in a positive or negative way.

Take advantage of your players expectations by flipping them on their head.

Outlining

Mindmapping

Def: a visualization of ideas, and the relationship between those ideas.

The goal of the mind map is to get your ideas down on paper in a visual format. Now that we have our mind map, we can turn those idea bubbles into a clear flowchart for our adventure.

Now that we have a mind map and/or flowchart for our adventure, we can move onto outlining.

Outlining可以很简单也可以很复杂直接上手,这里老师带了个简单adventure template用来参考使用.

Under each chapter in your document, add the following information:

Motivation: Why are NPCs, creatures, etc. motivated to do in this section?

Location: Where does this chapter take place?

NPC: Who are the NPCs characters may encounter?

Information: What information do the characters learn in this chapter?

Treasure: What loot or treasure may the characters earn?

Introduction

Many of them include the following components:

Overview/Synopsis

Background

Adventure Hooks

Dramatis Personae

Overview/Synopsis

This is where you’ll explain the whole adventure story, including any potential twists or late adventure developments.

Although you can think of this section kind of like the summary you’d find on the back of the book, you’ll want to take it one step further and include all of the narrative beats.

It’s not spoiling anything since the GM is the one reading and preparing the adventure.

Background

Writers often get stuck writing a Background.

All it really entails is anything that happened before the adventure begins.

This isn’t lore for lore’s sake; it’s information that directly pertains to the adventure.

For example, if your adventure features two villains who have a rivalry that the characters can leverage during the adventure, the background delves into the origins of that rivalry.

This is material that the GM can add to their portrayal of the NPCs or convey to characters upon successful investigation.

You can keep this section brief if you’re not sure what to write.

Think of opportunities to incorporate background information and lore that will give the GM plenty to work with, without overloading them with too much lore or worldbuilding that isn’t directly tied to the adventure.

Adventure Hooks

Many adventures include recommended “hooks,” or story seeds, for the GM to use to connect their player’s characters to the story.

These are optional, but make for a nice addition.

Essentially, these offer specific suggestions for how the characters get involved in the adventure.

For example:

- The characters are in a tavern (classic), and are approached by a mysterious stranger

- Something environmental happens where the characters are — an unexpected or cataclysmic event — and they now must investigate

- The characters spot an “Adventurers Wanted” post on a job board

Three to five adventure hooks are more than enough for a one-shot adventure.

You can get as inventive as you want, but keep in mind that not all GMs make use of adventure hooks (especially if they are using a one-shot adventure in the middle of a campaign).

Additionally, if you’re writing an adventure for an established setting, you can use adventure hooks to provide suggestions of how a GM can incorporate your story.

(For example, if you write an adventure set in the Nine Hells, you can suggest how to slot your adventure into the published module, Descent into Avernus, for GMs who are running that campaign.)

Dramatis Personae

This section is also optional but a nice way to succinctly convey NPC information to GMs.

This is where you briefly list and describe the notable NPCs that the characters may encounter in the adventure.

You can include their name, pronouns, physical description, and stats.

(you don’t have to include the actual stat block here; in many game systems, the stat of an NPC is bolded in-text:

For example — “Amira (she/her) is a warlock who uses the cultist stat block. She dresses in the all-black garb befitting her connection to the Great Old One.”)

It’s also helpful to include any motivating factors that may actively play a role in the adventure.

In D&D, there is a “traits/bonds/ideals/flaws” system used to flesh out NPCs enough for GMs to comfortably convey.

In CoC, players are encouraged to define their characters using their ideology, along with plenty of adjectives.

These approaches can be replicated across game systems, and might be good structures to emulate for NPCs in your adventures!

Sidenote

- TV Tropes

- Theme of a Story

- Different Genres of Literature

- Imposter Syndrome

- DriveThruRPG

- Thinkific

- he Best Design Idea White Wolf Ever Had (Villain Theory 101)

- Caverns of Thracia and Dark Tower by Jennell Jaquays.

- Abomination Vaults: The Ruins of Gauntlight by James Jacobs.

A modern dungeon adventure for Pathfinder 2 that puts the concepts we’ve talked about in this lesson into effect. - Jaquaying the Dungeon by Justin Alexander, who created the term “Jaquaysing the Dungeon” in this in-depth discussion of Jaquays’ adventures.

- 5 Room Dungeons by Johnn Four.

- Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman

- Players Making Decisions: Game Design Essentials and the Art of Understanding Your Players by Zack Hiwiller

- Game Design Concepts by Ian Schreiber

- How to write alt text

- Adobe reading order tool

- Acrobat Techniques

- Making accessible PDFs with Word

- Download NVDA