没想到还会用Mr.goose的tag.

报了滑铁卢continue education的课,挺水的,姑且记一记.

Mind mapping

Remember, 1) without verification, a fact is not a fact, 2) just because you see it in print doesn’t mean it’s true, and 3) things change.

Mind mapping process:

For every research project, you will need to create two separate mind maps: one for your writing topic, and the other for your research plan.

- Draw a circle in the middle of the paper.

- In the middle of the circle, write the name of your main topic.

- Draw 10 to 12 lines radiating out from the center circle, and at the end of each line, draw another circle.

- Now let yourself go. Fill in the blank circles with subtopics and related ideas. The point is to do whatever you feel like doing to get the ideas flowing.

The key is to work quickly. This is how you force your right and left brain to work together. If you try to do this in an orderly, logical manner, your right brain will be stifled. But if you open the mental floodgates, allowing yourself to write down whatever pops into your mind, your left brain will be so occupied with the task of writing that it will forget to squelch the right brain’s creativity.

Sources

Three kinds of sources: primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Primary sources are original materials from the original time period. These sources have not been rewritten or reinterpreted by anyone else. They include original documents (such as birth certificates, marriage licenses, court transcripts), personal interviews (in person, by telephone, or e-mail), photographs, diaries and letters, surveys, questionnaires and polls, and minutes of meetings.

Secondary sources consist of material you gather from published sources written after the fact, and are considered to be interpretations and evaluations of primary sources. If you are gathering information from primary sources, what you write as a result of that research will be a secondary source. Secondary sources include online and print newspapers, magazines, journals, biographies, and dissertations.

Tertiary sources are a further distinction of what some researchers might still call secondary sources. These tertiary sources are a compilation of facts and figures from both primary and secondary sources, and they include encyclopedias, almanacs, fact books (including trivia books), and dictionaries.

Difference between academic and anecdotal sources:

Academic materials consist of books, peer-reviewed journals, scientific studies, and databases—anything that has a scientific basis to back it up. Anecdotal sources are reports or observations without a scientific basis; in other words, anecdotal sources can be skewed by perspective.

Five Steps of Research

- Define your objective.

- Review what’s already out there.

- Design your research.

- Analyze your data.

- Draw your conclusions.

On this site you’ll find a list of glossaries for a wide selection of subjects.

This site has a comprehensive list of tools that writers will find most useful, everything from organizational and productivity tools to self-publishing tools.

Libraries

How to use libraries:

Public Libraries

First step to the library is to stop at the front desk or the information desk. Ask for a map or a directory of the library to help you get your bearings. A general idea of where things live in the library, combined with a good idea of what you’re looking for, will ease your way into researching mode.

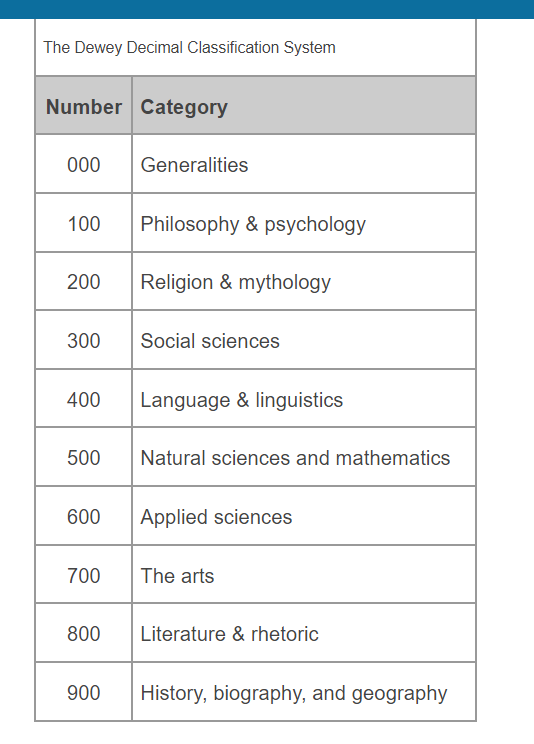

Remember the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) system? Here’s how the DDC system works:

When you retrieve a computer record of a book in the library, it will contain a call number that corresponds with the appropriate category in the DDC.

Contains in the academic libraries:

- Periodicals

- Reference Books

- Government Reports

- Databases (like the EBSCO database)

Academic Libraries

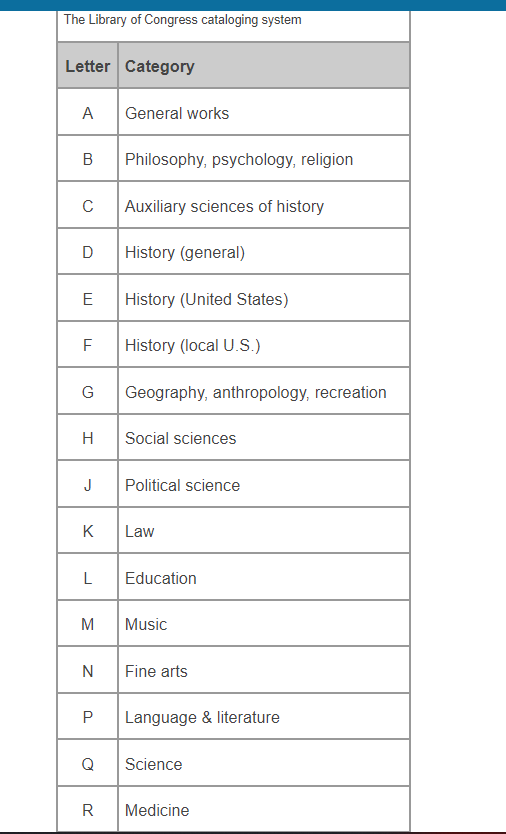

Academic libraries usually use the Library of Congress cataloging system rather than the Dewey Decimal Classification system. The LOC system is much more detailed than the DDC.

Contains in the academic libraries:

- Databases

Many academic libraries make databases such as LexisNexis available to anyone, but some will limit their use to enrolled students only.这个我记得,我在毕业后才知道…但是稍微上过一次,学校的database很牛逼,公司的财政收入都能看到.

虽然想找的是其他!

Specialty libraries

Specialty libraries exist in special places. Think museums, businesses, hospitals, government agencies, churches, and private organizations. Often such specialized groups maintain libraries of resources relevant to their specialty.

Although such specialty libraries might not normally be open to the public, sometimes all you have to do is ask. Even if you aren’t a member of the group, if you explain why you would like access to their library, chances are good that you’ll be successful. And even if you aren’t successful, you’ll probably get some good leads and advice.

OCLC WorldCat

WorldCat houses more than 49 billion bibliographic references from around the world. It identifies the library nearest you that has what you’re looking for, and you can also borrow materials through its interlibrary loan service.

This site offers a listing of the best free libraries on the Web.

If you’re interested in learning more about the LexisNexis legal, business, and news databases, check out this site.

This site offers an online catalog of Australian-published books, journals, newspapers, maps, photographs, music, photographs, films, and videos.

National Library of New Zealand

New Zealand’s national library holdings are cataloged in English and Maori.

This is Canada’s national library site. Like other national libraries, it has an online catalog of its holdings, and you can search in either French or English.

United States Library of Congress

Learn more about what the LOC has to offer. This is a dream site for researchers.

Here you can search a database of millions of books to either preview or read.

Personal interviews

Questioning Techniques

Skilled interviewers know that how they phrase their questions is almost as important as the content of the questions. There are two basic forms of questions: closed and open.

Closed questions often begin with who, when, what, and where, and can usually be answered with a single word or a short phrase. An even more refined form of a closed question is one that can be answered with yes or no. Closed questions give you facts, and they are easy for people to answer.

Open questions are designed to produce long answers. They require the subject to think and reflect, and they result in opinions and feelings. Open questions are the meat and potatoes of your interview. These are the questions you’ll labor over before the interview, and it’s important to put maximum effort into phrasing them to produce the desired results.

When I have a subject who starts to ramble, I tend to let it go for a while for two reasons.

First, it’s impolite to constantly interrupt, and second, you never know what you might learn.

If, however, after a few minutes, you realize that your subject’s ramblings about cleaning the birdcage are adding nothing to your interview, it’s time to redirect into something more substantive.

How do you do that? By employing a closed question. You’ll get a short answer, and you’re back in control of the interview and can change the subject.

Questioning Pitfalls

When you conduct an interview, it’s important for you to keep any preconceived opinions to yourself. Your questions should be bias-free, and so should the tone of your voice.

Another pitfall to avoid is the stupid question.

Think about your questions. Don’t insult the intelligence of your subject.

Also, when you’re formulating your questions, try to avoid starting questions with the word why. The word has an accusatory ring to it, and you might put your subject on the defensive.

One last trap to avoid is being bamboozled by psychobabble. If your subject starts tossing around psychological terms, ask what they mean to him or her.

Don’t be afraid of silence. You needn’t be concerned about filling every moment of the interview with talk. Sometimes a bit of engineered silence will give your subject the time needed to properly phrase an answer, to provide some additional information, or to even come up with that amazing quote interviewers crave.

Ask three times! If you’re asking a question that your subject doesn’t seem to want to answer or is trying to evade, ask it three times. Rephrase it if you have to, but when you ask the question the third time, your chances of getting an answer are excellent.

End-of-the-interview question. As your interview comes to a close, always, always ask this question: “Do you have anything to add, or is there anything I haven’t covered?” Nine times out of 10, you’ll get a piece of information that you never thought to ask about.

Thank your interviewee. I don’t mean just a polite thank you as you walk out the door—send a note, leave a voice mail message, or write an e-mail expressing your heartfelt thanks for the interviewee’s time and expertise. This has the added benefit of opening the door for follow-up questions in case you think of something you forgot to ask.

On this site you’ll find the Yearbook of Experts. Click the red book icon at the top of the home page, and it will open a PDF file containing an extensive directory of experts of just about any topic you can imagine.

Search for businesses that might have potential interviewees.

This is a search directory that can help you find specific interview subjects.

Reports and Studies

When analyzing them, however, be vigilant for bias. Employees of government agencies are sensitive to the fact that their jobs are subject to the whim of the current political party in office.

Scientific and Technical Reports

Annual reports are not subject to any laws and are created for the benefit of shareholders. As such, they strive to showcase the company in the best light possible, minimizing any possible shortcomings.

- Medical Research Reports

Most medical reports and studies are published in journals such as the Journal of the American Medical Association or the New England Journal of Medicine.

Another good place to find medical studies is through various medical associations, such as the Heart Association, the Alzheimer’s Association, and even the American Association of Retired People (AARP).

Putting Reports to the Test:

Find out who the author is.

If the author or sponsor of a report does not profit from the industry of the report, its credibility is enhanced.

Determine the purpose of the report.

Pay attention to the timeframe of the report.

Compare findings.

Turning Statistics into Prose:

Consider your audience.

Try to think the same way your audience thinks—figure out ahead of time how much technical detail will be appropriate, and write accordingly.

Plan your formatting.

But if your audience is more familiar with your subject matter, you can include your statistics in tables and charts. General readers like tables and charts too, but they have to be simple.

AnnualReports.com is the leading provider of online annual reports. It’s a free service, and you can find reports for just about any publicly traded company here.

SEC Filings

Enter a publicly traded corporation’s ticker symbol or name, and then click Search. On the next page, you’ll see a list of companies that match that name. Click the number to the left of the appropriate company to see its Securities and Exchange Commission filings.

This site is a starting point to travel to the various United States government agencies where you might find reports.

Government of Canada Publications

Here’s your starting point for locating government reports in Canada.

If you’re looking for government reports in Australia, this is a good place to begin.

History research

- The truth of history is shaped by the perspective of the presenter

- History has a way of evolving into mythology

Examples:

Encyclopedias:

- Britannica.com

- Encyclopedia.com

Wikipedia is a vast collection of articles that cover more topics than any print encyclopedia ever could. Be careful when you use it, though. The site is notorious for containing errors and mythical information.

笑死,空手搓俄罗斯历史事件.

Biographical Indexes:

- Biography Reference Bank

Bibliographies

Search Terms

Public Records

这一段内容比较多,会用comment记一下原文.

All of these records are brimming with personal information. Have you figured out yet what kind of research they are most useful for? You guessed it—genealogy research. If genealogy fits into any part of your research, these are the records you’ll want to access to help paint the picture of the people you’re writing about.

Vital Statistics

Birth, death, and marriage certificates.

If you’re writing about people who are real, you’ll often have some holes in their history. Sometimes, too, you’ll want to trace a person’s ancestors to help establish lineage and chronology. The natural starting place is birth, death, and marriage information.

- FamilySearch.org

- Ancestry.com

Court Records

Criminal and civil actions, bankruptcies, divorce cases.

Before you start a search of court records, your job is to find out two things:

- Which of these records are available to the public in your area.

- Where they are located.

Licenses

Doctors, lawyers, nurses, automotive repair dealers, contractors, and cosmetologists are just a few examples of licenses you can investigate in public records.

How can they be helpful? In addition to contact information, you can also find out if any professional complaints have been filed against a person.

Property Records

Grant deeds, quitclaims deeds, easements, liens.

Most real estate records are maintained in a city or county recorder’s office, clerk’s office, or some similarly named agency.

Public Works and Planning Records

Building permits, water, sewer, environmental impact reports.

To find these records, search online for your area’s government offices, or look in the government section of your telephone book. Look for departments of engineering, planning, construction, and environmental services. This should give you a starting point to help nail down the appropriate agency that has the records you want to see.

Public Office Records and Search Services

Campaign reports, statements of economic interest, lobbyist reports.

Very best source for interesting and relevant information on candidates, politicians, and other public servants comes from the forms they are required to file—forms that in turn become part of the public record.

- Campaign Contributions

- Statement of Economic Interest

- Probate

- Agendas and Minutes

- Professional Search Companies

This site offers a worldwide public records locater.

Vital records for countries other than the United States can be accessed here.

Here you can search for a local document retriever company anywhere in the United States. The site also has a good list of records available online.

You can do a quick-and-easy search on this site to find out if a company you’re considering hiring to help you with records’ searches has any complaints filed against it.

FamilySearch is a free site that can help you with vital-statistic searches. You do have to create an account, but there’s no charge to do so. If you’re interested in genealogy research, this would be a great place to start.

Ancestry.com is another great site for genealogical research. It requires a paid subscription, but you can try a 14-day free trial if you want to check it out. Also, the death index allows you to do a basic search for no charge.

Internet

- Search Engines

Advanced-search feature currently:

- From Google’s home page, enter a broad keyword into the search box, say, cheese.

- On the next page, look on the right side, toward the top, for an image of a gear.

- Click the gear image, and then select Advanced search.

The next page will have several boxes that will allow you to customize your search. Perhaps you want to see sites that contain only pepper jack cheese. You would enter cheese in the “all these words” box and “pepper jack” (in quotation marks) in the “this exact word or phrase box.” The results you get will be limited to only pepper jack cheese.

不过这种东西会随google更改,可能你在读这篇文章的时候没有那样的advanced search了.

- Directories

Directories are smaller than search engines, and search topics usually have to be broader. The benefit of using a directory instead of a search engine is that the results are almost always better tailored to what you’re looking for—that is, if what you’re looking for is somewhat general.

Directories are compiled in two ways:

By the people who maintain the directory.

By others who submit sites to the directory.

Dmoz and BOTW (Best of the Web) are probably the two most popular directories

- The Invisible Web

Philosophical Evaluation

Why was this site put on the Web? Is the site meant to inform, or is its intent to spread propaganda or one-sided viewpoints?

What sense of reality do you get from the site?

Could you find a better source somewhere else?

This highly regarded daily magazine is on the web and podcast network.

This Google site is an excellent tool for searching articles and case law about your subject.

Search for full-text magazine articles on this site.

List of Search Engines and Directories

This Wikipedia article lists dozens of the most widely used search engines and directories.

If you want to learn more about how to use Google’s resources, Google Scholar in particular, watch this video. It’s an older one, but it provides valuable information.

An international project that intends to digitize and make available (for free) primary material from around the world.

Surveys and Polls

Surveys

- Questionnaires

- Interviews

Polls

According to Priscilla Salant, author of How to Conduct Your Own Survey, an accurate sampling has four requirements:

- The sample is large enough to yield the desired level of precision.

- Everyone in the population has an equal (or known) chance of being selected for the sample.

- Questions are asked in ways that enable the people in the sample to respond willingly and accurately.

- The characteristics of people selected in the sampling process, but who do not participate in the survey, are similar to the characteristics of those who do.

You must determine three factors: how much error you can tolerate, the size of the population, and how varied the population is with respect to the characteristics of interest.

Writing Questions

- Are your survey questions phrased so that they require an answer from each respondent?

- Can respondents accurately and honestly recall the answers to your questions?

- Will respondents be reluctant to answer your questions?

- Are the questions easy enough so that respondents will answer all of them?

The TDM methodology basic elements:

- Minimize the burden on respondents by designing a survey or questionnaire that is attractive, has questions categorized in easily understood sections that flow vertically, and has personal questions at the end.

- Personalize your communications. If you plan to do a mailing, make sure it is personally addressed; if your contact will be by e-mail, try to have a name that goes along with the e-mail address.

- Engage your respondents in the process. Send out a letter or e-mail before the actual survey or questionnaire goes out, letting them know it’s coming and what it’s about. Also, build in some type of reward for respondents, even if the reward is limited to the expressed appreciation of the survey’s sponsor.

- Be scrupulous in your follow-up. Reminder postcards, e-mail messages, and telephone calls will increase the rate of response significantly.

The most successful surveys will consist of a series of four steps:

- A pre-notice letter or contact, letting people know the survey is coming and what it’s about.

- The survey or poll itself.

- A reminder notice sent approximately 10 days to two weeks after the survey is distributed.

- A replacement survey or poll.

Dr. Don Dillman’s Tailored Design Method

This is a more detailed description of some of the basic points of TDM.

This site has some additional information about some of the more specialized types of political polls.

A commercial site, this is where you can create a Web-based survey.

Summary of Survey Analysis Software

This site has links to several software programs designed to tally and analyze survey data.

The Pew Research Center routinely conducts surveys on every facet of life. Visit the center’s site to see its current surveys.

Survey Monkey is probably the best-known online survey site. You can create surveys for no charge, and you can access target audiences for a small fee.

Guerrilla

Guerrilla, or investigative, research.

Before you even begin using any guerrilla research tactics, ask yourself if the public—including you—really and truly has a right to know what you’re seeking to uncover.

- Directories and Reverse Directories

- Cell Phone Traces

- Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

- Personal Web Sites

- Military Records

- News Sites

The High Road: The Freedom of Information Act

FOIA document request.

Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the United States have all passed FOIAs to allow public access to a wide array of government documents.

The Middle Road: Personal Contacts

Follow the trail, for example LinkedIn or Facebook.

Finding Contacts:

Is there a gym near the building where the company is located? If so, watch to see if employees go there before or after work, or during lunch.

Ask for a tour of the company’s facility.

Many high schools have shadow programs that pair high school students with employees for a day to get an idea of what their job entails.

Pretend you’re someone you aren’t.

The Low Road: Dumpster Diving

Notice: If you’re considering sifting through someone’s trash, please check with your local police department to be absolutely certain you won’t be violating any laws.

Getting People to Talk

You could tentatively test the waters with some innocent-sounding questions.

Chances are, even if your contact has no direct information, he or she will probably know someone who does.

Blowing Your Cover

Sometimes it’s more productive to lay your cards on the table and hope for the best.

Whistleblowers

If you can make contact with a whistleblower, all your prayers will be answered. Every researcher craves a willing witness, a cooperative tell-all.

You can find a whistleblower in one of two ways.

- Hope that your contact will give you some clues to help you identify a potential whistleblower.

- Abandon all pretenses and let it be known that you are investigating the company. Let your name become familiar, and wait for the whistleblower to contact you.

On this site you can search for registered owners of Web domain names.

Although you must fax or mail your request for military records, you can learn about the process here and also download the necessary forms.

That’sThem is a free online service that will give you as much information as it has when you search on a phone number, either a landline or a cellphone. It has better success with landline numbers, but it’s worth a try to search on a cellphone number.

Copyright Law

The following list contains works that can be registered for copyright protection:

Literary works

Musical works, including accompanying lyrics

Sound recordings

Dramatic works, including accompanying music

Motion pictures and other audiovisual works

Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works

Architectural works

Pantomimes and choreographic works

Here are some things that cannot be copyrighted.

Works that have not been tangibly recorded; for example, an improvised stand-up comedy routine. Once the comedian writes down the improvisation, however, it then is copyright protected.

Titles of books, names, short phrases, and slogans. These items can be trademarked, but they can’t be copyrighted.

Ideas, procedures, methods, systems, processes, concepts, principles, discoveries, or devices. These items can be patented, but not copyrighted.

Items that are completely composed of common information and contain no original writing. As examples, the U.S. Copyright Office’s Web site lists calendars, height and weight charts, tape measures and rulers, and lists or tables taken from public documents or other common sources.

All 96 countries that are signatory to the Berne Convention agree that copyright protection is immediate and automatic upon creation of a work. You don’t have to register a work to gain copyright protection.

Writers should register their work with the copyright office anyway because registration is extremely helpful should you ever have to prove or defend your copyright.

When copyright protection expires, the work goes into the public domain and can be reproduced without permission (but not without attribution. The duration of copyright protection, however, varies from country to country. In Canada and Australia, it generally lasts from creation of the work until 50 years after the death of the author. If there is more than one author, the copyright doesn’t expire until 50 years after the death of the last surviving author.

Attribution is guided by three principles: ethics, copyright law, and courtesy to readers who wish to identify and further study your sources.

Formatting references:

| Academic Discipline | Style Manual |

|---|---|

| Humanities (for undergraduate students) | MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers |

| Humanities (for graduate students & professional writers) | MLA Style Manual & Guide |

| Social & Behavioral Sciences | Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association |

| History | Chicago Manual of Style |

| Sciences | CBE Scientific Style and Format |

| Medicine | American Medical Association Manual of Style |

| Computer Science | Microsoft Manual of Style |

| Business | Gregg Reference Manual |

United States Copyright Office

If you have any questions about U.S. copyright law, you should find the answers here.

How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work

This site provides information to help you research copyright holders.

Laws and information relating to Australia’s copyright law can be found on this site.

Here you’ll find information about Canada’s copyright laws.

This not-for-profit company will help you secure permission to reprint.On CCC’s home page, in the Get Permission box, enter the title or ISBN of the book you’re interested in.

Click Go , and if the title is among those administered by the CCC, you’ll get a list of the various editions along with a button to click for permission options.

MLA Works Cited: Electronic Resources

If you’re interested in learning more about the intricacies of referencing Web sites, this is the MLA’s version.

Writing process

If you’re struggling with trying to cram every teeny-tiny related factoid they’ve uncovered into their writing, answer these three questions (honestly):

- Is it relevant?

- Is it accurate?

- Is it repetitive?

Direct quotes.

When you use a direct quote, it must be verbatim; in other words, it has to be identical to the original. You cannot change words, spelling, or even punctuation.

If there is a word in a quote that is so unusual that you don’t think readers will grasp its meaning, you can leave it in its original state and place the Latin word sic in brackets immediately following the word. Sic means thus it is.

How to Edit/Revise (Add, Cut, Replace, Move around)

Try to schedule your time so that you’ll be able to put your work aside for at least a day or two before you start the editing process.

If you start your revisions as soon as you finish writing, your brain won’t have had time to relax and recharge. You won’t see areas that need improvement as easily as you would if you let some time pass.

Now let’s take the editing process step by step.

Title.

Does the title of your work give readers an idea of what’s to come? Does it adequately describe the contents of your work? Snappy titles aren’t always easy to come up with, but they are critical for motivating your readers to actually pick up your work.

Research question or thesis statement.

Make sure your purpose for writing is clear. If readers don’t get a good, upfront idea of what your problem or question is, they might not be able to sustain the motivation to continue.

Introduction.

Have you written a clear introduction that conveys the importance of your work and puts the thesis in context? And is it clear where your introduction ends and the body of the work begins?

Transitions.

Scrutinize transitions from paragraph to paragraph and from section to section. Make sure they flow smoothly and that the reader is carried along in a logical progression.

Order of material.

Research sources.

Does the research you’ve included truly support your thesis? Are your sources convincing or have you included some not-so-great sources just as filler? In fiction, the purpose is to advance the plot. In nonfiction and academic writing, the purpose is to make your point or prove your thesis.

Citations.

Balance.

Have you achieved a good balance between referenced sources and your own thoughts and insights?

Relevance.

Do you stay on topic throughout your work, or do you wander off into irrelevant material?

Conclusion.

Does your conclusion support your thesis? Think of writing as going from point A to B to C until you reach the desired conclusion. Readers should be able to easily follow your progression, and the conclusion is the payoff.

The truth is, I have yet to meet a writer who does not struggle for words from time to time (lol).

What distinguishes good writers from mediocre writers is that they work very hard to keep their writing fresh and original. Even when the words aren’t coming, they restrain themselves from resorting to clichés and tired colloquialisms.

Frequent mistake list

Between versus among.

As a general rule, between implies two persons or things, and among implies more than two.Who versus whom.

Lay versus lie.

Hopefully.

Look at this sentence: “Hopefully we’ll catch the train on time.” What is meant by this sentence is “I hope (or ‘it is hoped’) we’ll catch the train on time.” Remember this: Hopefully is an adverb meaning in a hopeful manner that needs to describe a verb, such as “She waited hopefully for a good grade.” Hopefully is describing the verb waited.Different from versus different than.

Different from is most often the correct construct, even though you will see different than frequently. Always use different from for simple comparisons, and save different than for when your ear tells you it’s better or it would simply be too cumbersome to do otherwise.Datum and data.

Although datum is technically the singular of the plural data, it is rarely used anymore. The plural data has evolved into a synonym for information, and thus is used as both a singular and a plural.

A word of caution, though: There still remains a clear distinction between the singular and plural versions of phenomenon (singular) and phenomena (plural), criterion (singular) and criteria (plural), and medium (singular) and media (plural).Affect versus effect.

Disinterested versus uninterested.

Disinterested means impartial, and uninterested means lacking interest. An easy way to remember the difference between the two is this: Judges are disinterested (impartial) but not uninterested (lacking interest) in the cases before them.Close proximity.

This is a phrase that writers love to use, but it’s redundant. Proximity means closeness, so the phrase close proximity actually means close closeness.Imply versus infer.

Imply means to suggest or express indirectly. Infer means to draw a conclusion. Only the speaker can imply, and only the listener can infer.Insure versus ensure.

Insure has the added meaning of protecting from financial loss. So if you’re writing about premiums and policies, be sure to use insure.More importantly.

Technically, this phrase is grammatically incorrect. More important is the proper form.Persuade versus convince.

Knowledgeable writers will convince (or create belief in) their readers of a fact, but persuade (or induce) them to do something.

This is an interesting site to browse. It’s a huge expansion of the word usage chapter in this lesson.

Updated continually, this CIA-produced resource has information on more than 250 countries and regions. You’ll find some amazing things here.

The Modern Researcher

by Jacques Barzun, Henry Groff

Wadsworth Publishing, 2003.

The Craft of Research

by Wayne Booth, Gregory Colomb, Joseph Williams

University of Chicago Press, 2003.

How to Conduct Your Own Survey

by Priscilla Salant, Don Dillman

John Wiley & Sons, 1994.

Researching Online for Dummies

by Reva Basch, Mary Ellen Bates

For Dummies, 2000.

For dummies系列算是我高中的救星…怀念…